Integration

Katarina Hirschberg Bryn Mawr College Class of 2025 & Grace Diehl Bryn Mawr College Class of 2027

Introduction: The Complicated Integration Process at the YWCA

When looking at the path to the integration of the YWCA, the process was far from clean-cut. Legally speaking, the integration charter mandating that all YWCAs be integrated was not passed until 1946. However, as early as the 1920s, events and practices involving both Black and white members are evident.

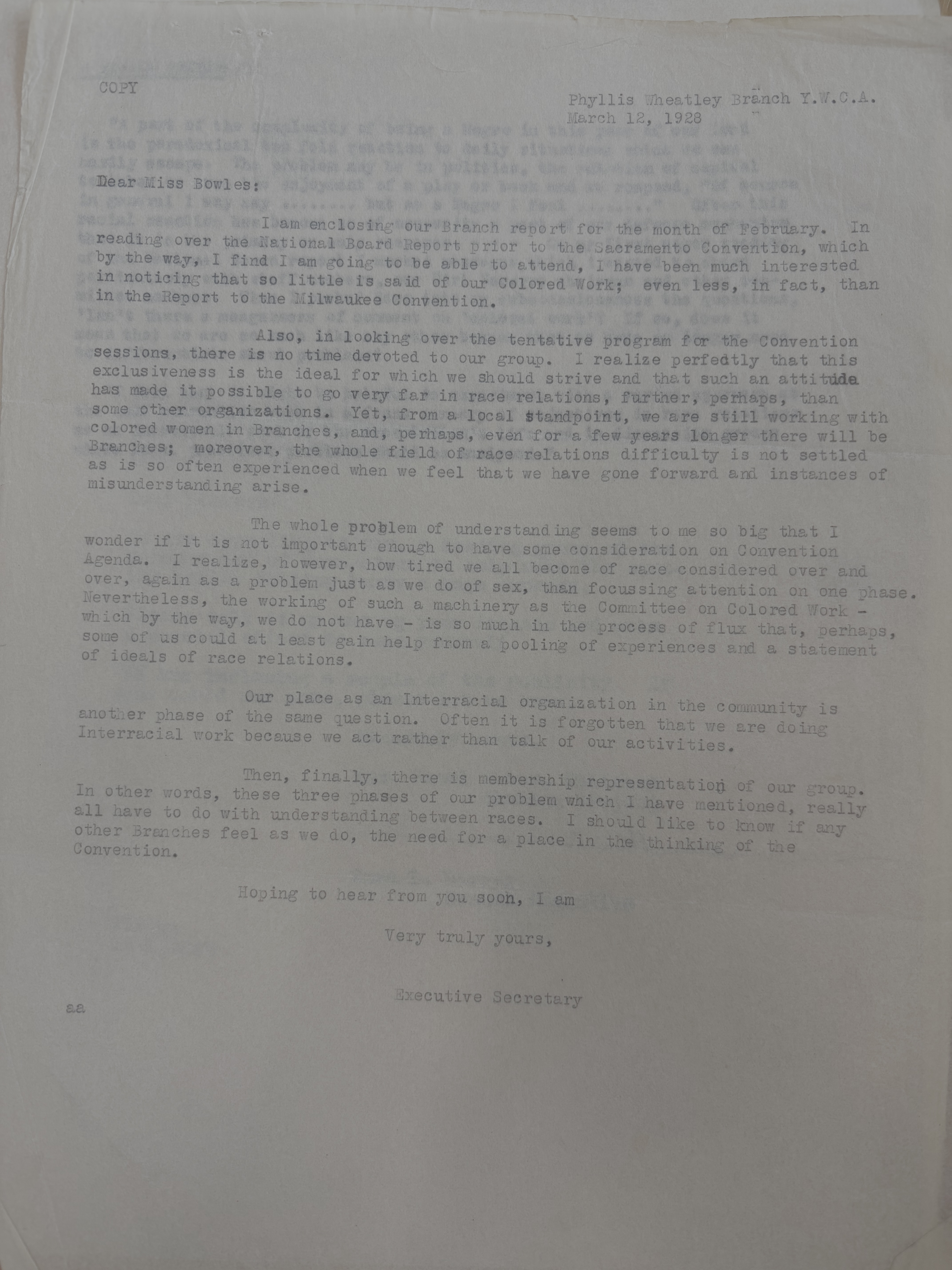

An example of the non-linear process is seen in this letter from 1928, almost 20 years before integration became policy, which notes interracial proceedings but a lack of recognition.

1 In 1928, a letter from the executive secretary of the 6128 Building was sent to the main branch concerning an upcoming convention. In the program for the convention, the executive secretary noted that there was “no time devoted to our group,” and went on to note that, “often it is forgotten that we are doing Interracial work because we act rather than talk of our activities.” With this letter, it is clear that integrated activities happened, but were not discussed or officially noted. Still, activities were not enough to give Black leaders a seat at the table or for their proceedings to be highlighted at a convention. At the same time, it is important to acknowledge the advanced work that was being done in terms of interracial projects and the fact that 1928 is incredibly early to see evidence of integrated proceedings.

The Interracial Charter and Beyond

The Interracial Charter adopted by the Germantown YWCA in 1946 mandated that all facilities and activities be open to all women and girls in the community - regardless of race. The swimming pool created some initial issues due to the physical contact its activities would require between people of different races. Shortly after the policy was put into place, Colored Branch leaders began assuming leadership positions in integrated boards so as to have more input into the process. Still, some positions held titles without real power, and all voices were not necessarily valued equally. Further, issues arose with class differences in clubs and people tended to remain within their groups regardless of the opportunity to integrate.

After the initial movement towards integration, leaders realized the need for a governing body that oversaw the process. In 1948, the Integration Committee was created and outlined recommendations for the future of the main YWCA and the Colored Branch. Included in these recommendations were plans to have interracial staff, accessible clubs, and more activities hosted in the Colored Branch. Some of these recommendations were met with apprehension by Black leaders due to a loss of their space and community in favor of integration. The 6128 Building became a center for clubs and groups and staff were required to move to the 5820 building to serve in the new administration building.

Integration as a “Success” and the Closure of the 6128 Building

As early as 1949, the director at the time, Gladys Taylor, reported integration to be a success in the YWCA community, and Black leaders began to assume leadership positions. However, soon after this, budgetary concerns led to the closure of the 6128 building in 1952. With that, the community had varying feelings. White leaders celebrated the triumph of integration, excited about the prospect of hosting all activities in one building. Black leaders and members, on the other hand, felt tragedy and a loss of power and community, some going as far as refusing to go to the 5820 building.

As a whole, this process of integration was not linear, and far from perfect. Setbacks including the lack of positions given to Black leaders as well as white directors projecting images that were not completely accurate led to struggles over power and community. In the end, the closure of the 6128 building was seen by the Black community as a major loss, and although integration was successful on paper, lasting memories about the process vary drastically. Still, the choices of leaders of the YWCA to integrate much earlier than mandated worked to create community in Germantown that crossed racial barriers.

-

[Letter regarding Convention proceedings, 3/12/1928], [Box 25, Folder 8], Young Women’s Christian Association of Philadelphia (Pa.), Germantown Branch Records, Acc. 877, 280, PC-46, PC-89, Special Collections Research Center, Temple University Libraries, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. ↩