Before a single actor appeared onstage to perform the play, the Athenian audience of Euripides’ Medea would have been aware of the fundamental events of Jason’s quest for the Golden Fleece as well as Medea’s role in assisting him. Ancient Greek myth in general consisted of a body of stories with variants built in, rather than a set untouchable narrative, and in many ways, ancient tragedy allowed a playwright to put their own spin on an established story and to refashion a myth which was familiar to the audience while offering something new. Euripides not only borrowed from earlier stories, but his Medea took on a life of its own and became source material for new interpretations to come. For example, Euripides’ version likely informed Seneca’s 1st century CE tragedy of the same name, which takes the conflicted but complicit Medea to a new degree of villainy, as, unlike in Euripides’ version, she kills the children on stage in front of Jason.

Modern interpretations of the tragedy reveal the enduring appeal of Medea as symbol of female voice, oppression, and colonization.1 Feminist tones of the play were certainly felt when passages of a translation by Gilbert Murray were circulated at women’s suffrage meetings in London, and the gendered connotations of the characters and their dynamics have been highlighted through contrast. For example, the genders of the characters are swapped in Polendo and Theater Mitu’s 2010 collaborative stage adaptation. In the staging of Ninagawa’s Medea, a male Medea practices a Kabuki technique in stripping off a female-coded costume to reveal heroic attire, and in McDonald’s Medea, Queen of Colchester, Medea is characterized as a drag queen and stepparent to the doomed children. Other versions have used Medea’s suffering as symbolic of an even broader type of violence, for example, Müller’s opera, Medeamaterial, in which Medea functions as a symbol of destruction of the earth.

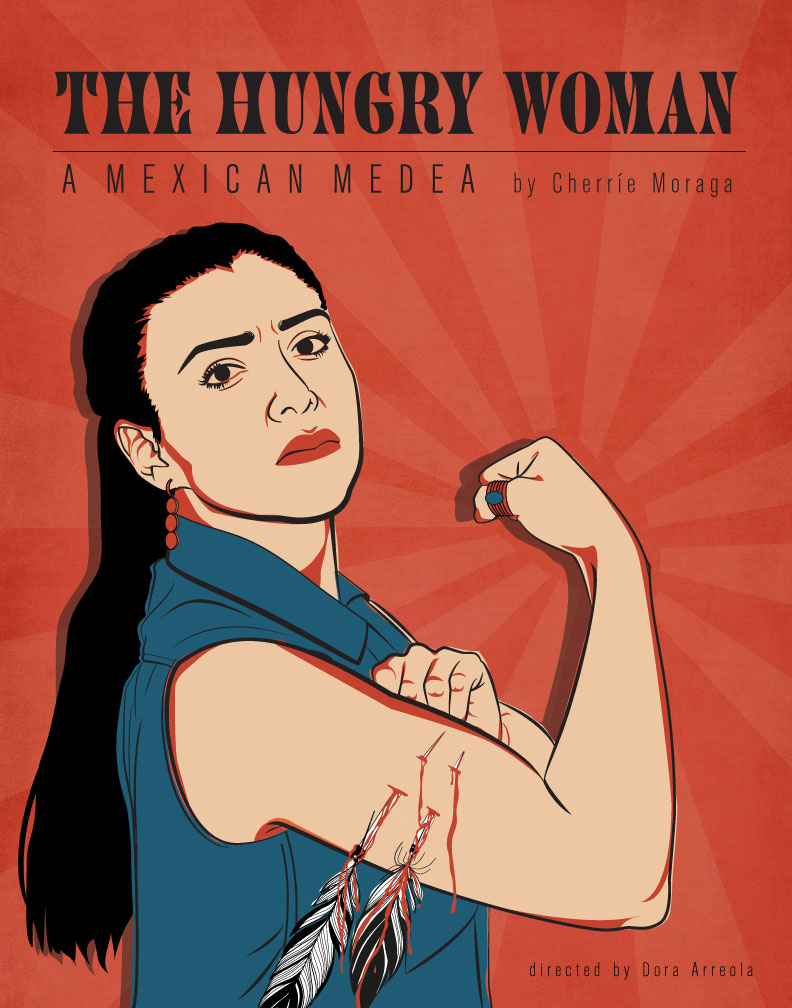

Most prominently, however, modern retellings have used Medea’s character to address racial inequities and violence across the world. On the popularity of Medea adaptations, Wetmore writes: “Medea is the most popular figure in the Afro-Greek world.”2 Guy Butler’s Demea, a criticism of apartheid, casts a white Jason opposite a black Medea, though segregation at the time the play was written made staging this interracial performance impossible for decades. Brett Bailey’s 2012 direction of the play MedEia portrays Medea as an African refugee who faces mistreatment within the European immigration system. The trauma of immigration is also depicted in Alfaro’s Mojada: A Medea in Los Angeles, and Lenormand’s Asie changes the names of the characters to tell the story of French colonization. Throughout these varied reimaginings of Medea’s story, the commonalities of racial violence and oppression emerge.

This is only a sampling of the many retellings and the many Medeas. Sarah Iles Johnston attributes Medea’s appeal to her complexity, as she is a character who resists resolution or easy description.3 In Medea, A Performance History, the authors offer that it is the theatricality of her character which makes Medea such a fascinating subject, as she shows an ability to prostrate herself before Jason one moment then loom over the stage as a goddess of retribution the next. These many interpretations highlight the relevance Medea holds as a symbol of marginalized individuals and groups. From the first performance of Euripides’ Medea in Athens in 431 BCE, to performances of James Ijames’ Media/Medea presented at Bryn Mawr College and the Community College of Philadelphia in April 2023, the story and these characters have meant much to many, and will hopefully do so for millennia to come.

Learn More

- For an interactive resource with images, video, and audio clips of many of the productions referenced here, check out the free eBook Medea, A Performance History by Fiona Macintosh, Claire Kenward, and Tom Wrobel.

- For more on the many Medeas, read Medea: Essays on Medea in Myth, Literature, and Art edited by James J. Clauss and Sarah Iles Johnson (Princeton University Press, 1997).

Audrey Wallace recently received her Ph.D. from Bryn Mawr College in Greek, Latin, and Classical Studies in 2023, where she also received her M.A. in 2017.

-

Refer to Medea, A Performance History under “Learn More”. ↩

-

Kevin J. Wetmore Jr. “Black Medea,” Black Dionysus: Greek Tragedy and African American Theatre, (North Carolina, McFarland, 2003), 137. ↩

-

Sarah Iles Johnston, “Introduction,” in Medea: Essays on Medea in Myth, Literature, and Art, (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1997), 6. ↩