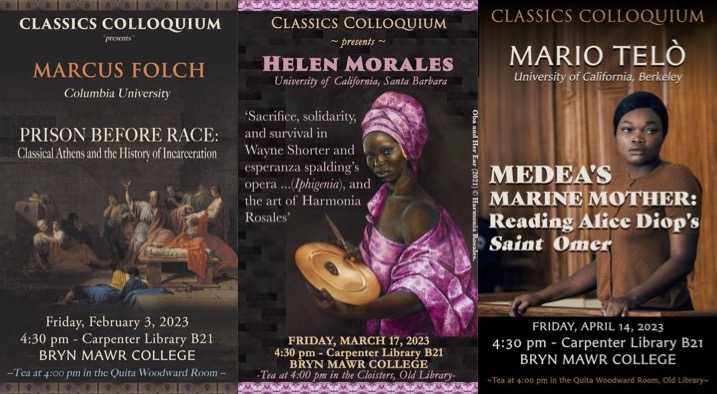

This spring, three esteemed scholars were invited to Bryn Mawr college to take part in the Classics Colloquium, a weekly speaker series open to all members of the community and sponsored by the Department of Greek, Latin, & Classical Studies. These presentations highlighted the broad scope of the Greek Drama / Black Lives collaboration, and examined material ranging from Platonic Greek texts contemporary with Euripides’ Medea to a 2022 French film, Alice Diop’s Saint Omer. Each talk explored the reception of ancient texts and provided additional avenues for engaging with the conversations raised by the Media/Medea production.

On February 3rd, Marcus Folch presented the talk, “Prison Before Race: Classical Athens and the History of Incarceration,” in which he examined ancient evidence for imprisonment’s physical and spiritual effects. Folch, in an attempt to trace the social perception of the prisoner from outcast to hero, examined the purposes behind prisons throughout history, as they were used both as a form of punishment and as a tool for reformation. Prisons also served a custodial function and the restriction associated with imprisonment operated as a form, and even symbol, of control. Imprisonment is used in Platonic texts to describe hindrances to one’s philosophical journey, but it was also used as a very real form of social control by those in power to target groups deemed dangerous or disruptive. At the end of his talk, Folch reflected on the lack of historical evidence for female imprisonment, even though women were not exempt from legal prosecution or punishment. He proposes that prisons served as a form of enforcement of social behaviors which were only allowed to men in the first place, and that the social seclusion and exclusion faced by ancient women served as a form of imprisonment in its own right.1

Helen Morales moved away from imprisonment to its opposite, asking “Where is the liberatory potential of Greek tragedy?” In her talk on March 17th, entitled “Sacrifice, solidarity, and survival in Wayne Shorter and esperanza spalding’s opera …(Iphigenia), and the art of Harmonia Rosales,” she discussed new artistic recreations of Classical material. She explained how Harmonia Rosales’ work, which uses the aesthetics of Renaissance art as well as the content of Christian stories and Greek myths, aims to decenter whiteness from these depictions and narratives. By including West African deities, as well as depicting imagery of the slave trade, Rosales highlights the whitewashing of origin myths. Morales also looked at Shorter and Spalding’s 2021 …(Iphigenia), a new opera which portrays the patriarchal dangers which loom over ancient heroines. This staging of the Iphigenia story and its creation of many Iphigenias emphasized the multiplicity of the central character and provided one possible answer to Morales’ central question. By presenting a story which resists resolution, Morales offers, suspense may grant a contemporary audience new power over a traditional story.2

Mario Telò raised a similar argument about the benefit of reframed narratives when he traveled to Bryn Mawr on April 14th for his talk, “Medea’s Marine Mother: Reading Alice Diop’s Saint Omer”, which considered the link between Medea and a film inspired by true and tragic events. In this film, the audience watches a trial of a woman accused of infanticide through the eyes of a pregnant journalist. The film explores many of the themes of Medea: the female outsider, empathy in the face of violence, complicated relationships between mothers and their children, and even a resonance with Media/Medea specifically, as the lack of a depicted verdict leaves the future of the characters up to the imagination of the audience.

Though the performances of Media/Medea at Bryn Mawr and Community College of Philadelphia have now wrapped, the collaboration behind this production has helped open a discourse with unlimited applications. These topics were broad in scope, material, and approach, all while seeking a greater understanding of both the pain and the potential reflected in the ancient material. All the works cited and presented by these authors reveal the power, and intertwined nature of the two facets of the larger project: “Greek Drama” and “Black Lives.”

Learn More

- Intrigued by Marcus Folch’s discussion on imprisonment? You may want to check out Plato’s Phaedo and Republic, Against Timocrates by Demosthenes, Discipline and Punish: The Birth of a Prison by Michel Foucault (Translated by Alan Sheridan. Random House. 1977), and Folch’s 2021 article “Is Red Figure the New Black? The Imprisonment of Women in Classical Athens” (Ramus 50.1-2: 45-67).

- Interested in the use of Classical material in contemporary art, as introduced by Helen Morales? Take a look at the paintings of Harmonia Rosales, particularly “Birth of Oshun” (2017), “Oshoshi Recieves His Crown” (2019), “White Lion” (2022), and “Master Narrative” (2023). For reading material, check out In the Wake: On Blackness and Being by Christina Sharpe (Duke University Press. 2016), and In the Black Fantastic by Ekow Eschun (MIT Press. 2022).

- For more on the cinematic intersections with Medea that were analyzed by Mario Telò, track down the 2020 article “Strange Intimacies: Reading Black Maternal Memoirs” by Jennifer Nash and Samantha Pinto (Public Culture 32.3: 491-512), Judith Butler’s 2006 chapter “Critique, Coercion, and Sacred Life in Benjamin’s ‘Critique of Violence” in Political Theologies: Public Religions in a Post-Secular World (Edited by Hent de Vries and Lawrence E. Sullivan. Fordham University Press. 201-219), and Blue Black by Glenn Ligon (2017).

Audrey Wallace recently received her Ph.D. from Bryn Mawr College in Greek, Latin, and Classical Studies in 2023, where she also received her M.A. in 2017.

-

For more on the historical evidence of female imprisonment, see Folch’s recent article, “Is Red Figure the New Black? The Imprisonment of Women in Classical Athens,” Ramus 50, no.1-2 (2021): 45-67. ↩

-

Iphigenia’s fate is even more uncertain than that of Medea, and Euripides wrote two plays about her, each of which has a drastically different ending. In Iphigenia in Aulis, Iphigenia discovers that she is doomed to be sacrificed by her father, in order to lift a divine curse and allow his troops to sail to Troy. Though she seems to walk toward this same fate in Iphigenia in Tauris, the play instead presents her magical escape from death. ↩