The Franklin Institute Item Info

- Title:

- The Franklin Institute

- Creator:

- Isabela Jimenez

- Date Created:

- 9/9/2023

- Subjects:

- architecture

- Location:

- The Franklin Institute

- Latitude:

- 39.9584905083689

- Longitude:

- -75.1730810558029

- Rights:

- CC BY-NC

- Standardized Rights:

- https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/deed.en

The Franklin Institute: A Monument to American Scientific Culture

Introduction

The Franklin Institute stands as one of the founding organizations of the United States’ science and industrial fields. This organization was critical in forming and helping define what the inclusion of science in education and civic life would grow to look like. The historic role of the Franklin Institute, as well as its prominent modern influence, makes it an interesting object of study. The Institute has long functioned as more than a museum of science, but a public statement about what knowledge should mean in American life: practical, accessible, and tied to the moral responsibilities of citizenship. Examining the building’s form, materials, and historical backgrounds shows how architecture can shape the public meaning of science from the nineteenth century to the present.

Physical Attributes of the Building

While the Franklin Institute’s physical form primarily follows the Beaux-Arts style, several elements of the facade illustrate the Roman influence and Classical Revival used in architect John T. Windrim’s design. The exterior features a wide staircase met by six columns with ornamented capitals, all made of stone. The building as a whole is highly symmetrical, with pilasters and intricate molding adding texture to the otherwise relatively flat two-story facade. The words “In Honor of Ben Franklin” make the intentions of the building clear – a message which is reflected upon entry into the rotunda, which serves as the centerpiece of the architectural space.

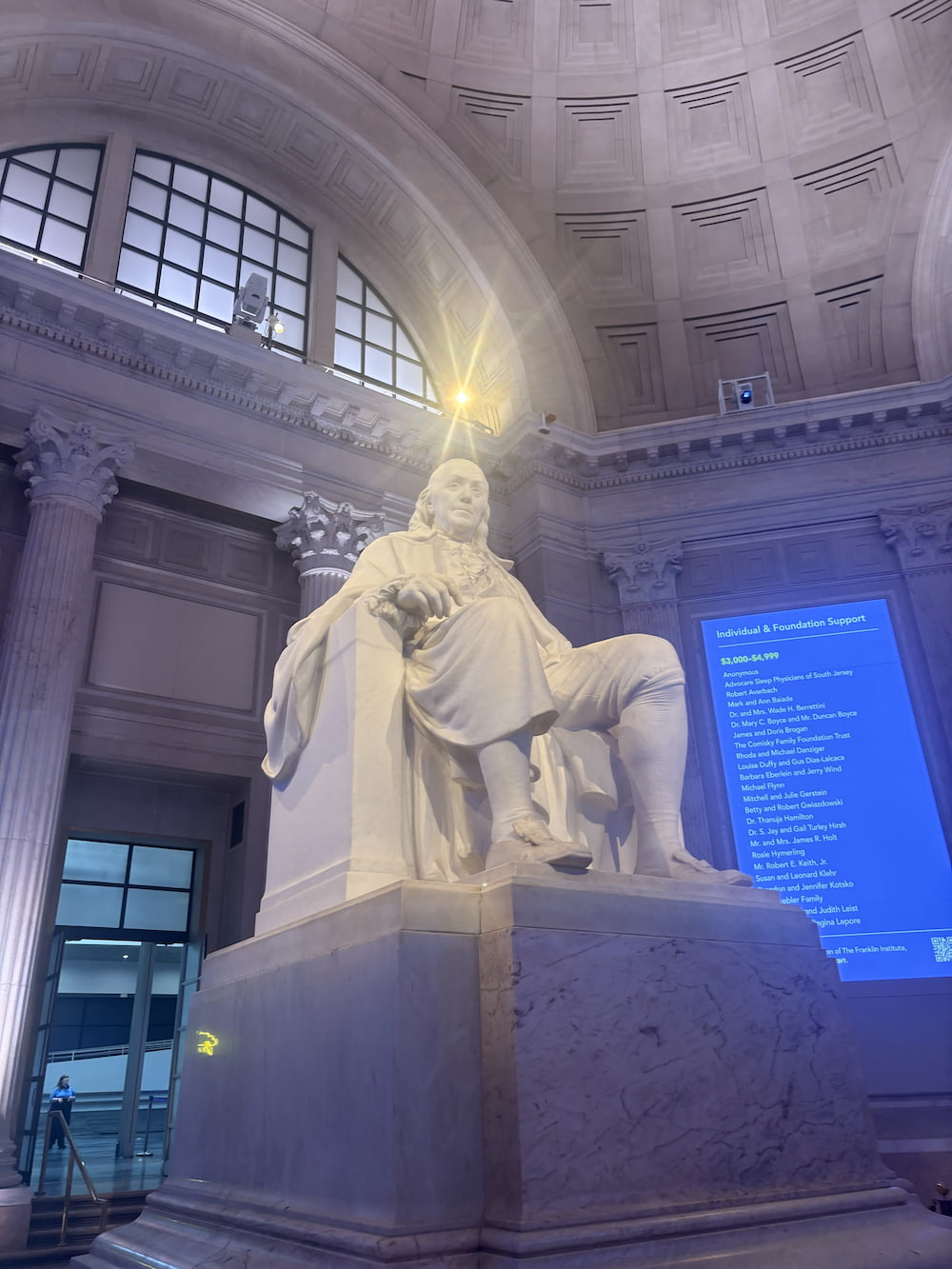

First opened in the building’s rotunda in 1938, the Ben Franklin National Memorial within the Institute is modeled directly after the Pantheon in Rome. The 82-foot domed ceiling of this space is self-supporting, making this an impressive architectural feat due to its weight of 1,600 tons (Jmontefusco).1 While this rotunda was far from the first American dome to be inspired by the famous Pantheon’s design, it embodies and pays tribute to the historic dome’s architectural legacy. The coffered texture on the entirety of the dome duplicates the design of the Pantheon almost exactly, adding a feeling of lightness and interest to the space while serving important structural functions as well (Mark and Hutchinson).2

While the rotunda is not perfectly symmetrical, the overall balance that Windrim creates embodies the principles of classical architecture, which emphasizes visual harmony. Columns, pillars, cornices, details, and even the walls and floor were created using rare marbles, most sourced from Italy, Portugal, and France, and core to classical architectural design (Jmontefusco).3 These architectural details demonstrate clear Classical Revival and Italian influences, as seen in the embellishment atop the cornices, the fluted columns, and the visual symmetry of the space.

Arched windows and a skylight allow plenty of light to flow down into the space, illuminating the statue and casting intricate and intentional shadows on the walls and floor. This decision by architect Windrim further enhances the space’s feeling of prestige and grandeur, reflecting the respect and celebration of Benjamin Franklin’s life that the Institute strives to capture. While in the original Pantheon in Rome, this skylight is left open, allowing the natural air into the space, in the Franklin Institute’s rotunda, Windrim closed off this ceiling in a rational decision to protect the memorial from the elements (Hannah, Robert, & Magli).4

Beneath the coffered ceiling dome sits a centerpiece statue of Ben Franklin. This eye-catching memorial is carved from white Servazza marble, a stone associated with the most prominent Roman statues and buildings, and features Franklin seated on a pedestal above viewers looking down upon visitors (Britannica Academic).5

The figure of Franklin is carved using classical sculptural design methods, further emphasizing the space’s connection to classicism and Italian art and architectural tradition.

Provenance and Creator Background, Relationship to Environmental and Historic Context

The Institute was first founded in 1824 by Samuel Vaughan Merrick and William H. Keating. Merrick was an American manufacturer and the first president of the Pennsylvania Railroad. Born in Massachusetts in 1801, Merrick moved to Philadelphia to work with his uncle and study engineering. He founded the Franklin Institute with Keating, who was an American geologist and University of Pennsylvania alumnus. Their goal was to promote mechanical arts, which initially happened through public lectures, journals, and exhibitions. To reflect this educational purpose, both John Haviland and John T. Windrim designed structures that visually communicated the Institute’s commitment to innovation and public learning.

Because the Franklin Institute switched locations, it had two main architects, John Haviland and John T. Windrim, with Haviland designing the original building. Haviland was born much earlier than Windrim in 1792 and designed the original Franklin Institute at 15 South 7th Street. Even though his design is less modern and not currently used for its original function, his architectural background remains important to understanding his work, as he was known as one of the most important architects working in Philadelphia in the second and third decades of the 19th century. Haviland was born in England and studied under a London architect, James Elmes. Afterwards, in 1815, Haviland met George von Sonntag and John Quincy Adams in Russia, which encouraged him to work in the United States.6

His success can be seen in the fact that he published many books, which was a “landmark event in American neo-classical architecture”. His books were one of the earliest architectural pattern books written in North America, and were the first to include both Greek and Roman orders. This highlights how crucial books were in spreading artistic and architectural knowledge. Beyond communicating architectural styles, the publications taught architectural knowledge at a moment when America lacked formalized architectural training, allowing Haviland’s neoclassical techniques to shape the broader built environment of Philadelphia. After the success of his publications, he took on important projects such as the First Presbyterian Church in 1820, Saint Andrew’s Episcopal Church in 1822, and the original Franklin Institute in 1825. His original design was strongly influenced by Greek architecture, which stood out against the sea of red brick buildings with its blue marble walls. His reliance on Greek forms was not only stylistic, but ideological. In early nineteenth-century Philadelphia, Greek Revival buildings symbolized civic virtue and rationality, values that the Franklin Institute hoped to associate with scientific education. After this series of successful projects, Haviland eventually fell into bankruptcy when he started to speculate in his own projects and move money around. As a result, he never secured large projects afterwards, outside of designing state prisons in New Jersey and New York.7

The current Franklin Institute building was designed by John T. Windrim. Windrim was born in 1866, right after the end of the Civil War. The year after he was born, his father, who was also an architect, had a successful entry in the Masonic Temple competition. Because it was an important and influential art show, this helped boost his family’s reputation and grow the architecture firm owned by his father. Windrim began studying business and architecture in 1882, and eventually inherited his father’s highly lucrative architectural practice. This allowed him to design many commercial and public projects, gaining him visibility. In 1889, when his father was appointed Supervising Architect of the US Treasury, Windrim took over and had a larger role in the firm. He became “the best-known Philadelphia practitioner”8 of the classical revival style. However, in the following years, it became difficult to distinguish his work from the rest of the firm’s due to the large number of employees who all had similarities in style. Overall, the firm was very financially successful, unlike many other firms at the time, which were largely based on residential commissions.9

Windrim designed the new Franklin Institute after it moved from its original location. His design included a square building surrounding the Benjamin Franklin Statue. However, only two of the four wings in the design were built. Despite the effects of the great depression, his grand design of the memorial, a 20-foot-high statue modeled after the Pantheon in Rome, was able to be built. The direct influence of Roman architectural styles can be seen in the marble material directly imported from Italy, as well as the columns and domed ceiling. By centering the Institute around a grand memorial court, Windr, transformed the building into both a museum and a civic shrine, linking scientific progress to the moral virtues embodied by Benjamin Franklin.

The first Franklin Institute had a major role in promoting the sciences in early Philadelphia. Not only was there important research that would further the development of the city, but their educational programs and exhibitions tied the institute to Philadelphia’s social environment. By displaying machines in ways that are easily understandable, it heavily stimulated domestic consumption and, therefore, production. Additionally, it promoted friendly competition, where the producers of these technologies could compete at the exhibitions for prizes or medals.

Materials, Techniques, Methods, and Construction Processes

The architect and supervisor of the project was John T. Windham, who designed the building in 1929 and oversaw its construction between the years of 1929 and 1934. The Ben Franklin National Memorial’s domed rotunda is the standout architectural feature of the space, and was heavily inspired by the Roman Pantheon in both its techniques and aesthetics. The Pantheon, built between 118 and 128 A.D., is widely acknowledged as a cornerstone of the Roman architectural revolution, which was made possible in part by the invention of new high-quality concrete (Wixom).10 This new material expanded the scope of possibilities in creating curved architectural designs at an unprecedented scale. Additionally, this material technology is combined with the strategy of creating concentric rings in order to better support the weight of large-scale arches. While scholars debate whether or not these new materials and architectural techniques were in fact necessary to allow for the creation of structures at the scale of the Pantheon, the building nonetheless captured the eye of architects, scholars, and passersby alike due to its revolutionary scale and design, whether or not the techniques it employed were truly crucial to its design (Mark & Hutchinson).11

The Rotunda of the Franklin Institute employs similar architectural techniques to the Pantheon, resembling this famous Roman structure in both appearance and structural design. Windrim was directly inspired by both the techniques and details of the Roman dome, as can be seen through the comparison of images of each. The grandeur of scale and detail combine in both structures through meticulous construction, although the original design was scaled back due to the onset of the great depression. Over the course of five years (1929-1934), construction took place, combining Beaux-Arts principles with classical construction methods (Linker).12 Modern additions, including the Karabots Pavilion, have since been added, although the original construction remains the same.

Purpose, Existence, and Evolution of the Item

Through its existence, the Franklin Institute has continued to evolve, adapting to the changing needs of the country while maintaining its fundamental commitment to the development of scientific curiosity and education. The initial goal of the Franklin Institute’s founding was centered on professionalizing the sciences and the engineering arts, looking to formalize an academic path for the sciences, it served a crucial role in shaping the early American scientific and industrial cultures.13 One of its main functions was the education of the public, in particular mechanics and engineers, through different methods such as lectures, practical exhibitions, a high school, a library, and a research journal. During the 1820s, the Franklin Institute emerged as a part of the growing industrial and scientific community. It was founded by Samuel Vaughan Merrick and William H. Keating , who saw it as a way to combine the intellectual inquiry involved in experimental physical sciences with the mechanical and industrial work that was needed to uphold the growing nation.14 Apart from conducting experimental investigations, the institute also created a place where the public, both those who already studied the sciences and those with little to no previous exposure, could freely interact and engage with these new technologies. This accessibility to cutting-edge innovations reflected the way in which scientific pursuit, industry, and innovation were becoming central and helped shape the evolving American identity in the very early stages of nation-building.

The Franklin Institute was founded as a nonprofit organization overseen by a board of trustees.15 Over time, the role of the Franklin Institute shifted in response to the broader changes and transformations in the landscape of the American sciences and industry. University careers took over the space the Franklin Institute had originally filled in educating the first engineers of the United States, with corporate research laboratories and university careers replacing the ‘mechanic’ model that had been characteristic of the Franklin Institute’s education.16 With such changes, the Institute adapted by redirecting some of its educational focus towards the public, creating exhibitions and hands-on learning opportunities that were open to audiences, nonetheless, it did not abandon the research traditions it was founded on. The Institute became one of the first interactive museums in the United States, showing in part a changing relationship within the Institute between science, industry, and public life.17

The development of the Franklin Institute, from a focus on local, industrial learning to fomenting a national culture of public scientific education, reflects how the institute has changed to meet the needs of a growing country, as well as revealing what was prioritized as these national needs during the early years of the United States. The current board of trustees is also reflective of the Institute’s mission, composed of members of the city government, leaders from the scientific and educational communities, and representatives of major industries, it has grown to continue guiding the Institute in its commitment to scientific engagement and public scientific education.

Interpretation, Continuity, Message

As Thomas Coulson, historian of technology and science, writes in ‘The Franklin Institute from 1824 to 1949’, an institution which presents and brands itself “In honor of Benjamin Franklin” must operate at a level of public respect, acclaim, and rigor that is befitting of its namesake. In his own words, “It must be truly American in spirit and performance.”18

This expectation has shaped the Franklin Institute’s self-presentation ever since its founding, with both Benjamin Franklin and America’s legacies resting on the institute. Despite the way in which the institute has constantly evolved to match its needs of the moment, its mission has remained a constant, rooted in its original purpose of advancing the public understanding of scientific knowledge in a young nation and promoting a passion for learning about science and technology.

The enduring commitment the Institute has had to education and discovery has guided the Franklin Institute through its many changes and challenges it has faced throughout its history. This commitment towards scientific pursuit, promoting the classical ideas of rationality and the civic virtue of education, is an aspect that is expressed not only through the programming of the institute but also through its architectural design. The monumental neoclassical structure presented for the Franklin Institute, modeled after the Pantheon in Rome, draws on the visual language of symmetry and rationality that this architectural style invokes, through its design transmitting ideas of public virtue and rational inquiry.19 The architect’s choice to draw on Italian classical references is deliberate, the longstanding associations that this style has with intellectual refinement and civic life transmitted the message and founding mission of the Franklin Institute perfectly. By adopting these visual cues, the Institute visually aligned itself with the aesthetics of progress and democracy, which the national government had already been using for state buildings. Additionally, modeling the Institute after a Roman temple through its imitation of structures like the Pantheon elevates the pursuit of knowledge and science to the status of a sacred practice, both setting the precedent but also reflecting the ideals behind the founding of the United States as a secular nation that advocated for progress.

Apart from the dome, the Statue of Benjamin Franklin that is placed under its center stands as another stark example of the adoption of classical design that serves to reinforce this message. Franklin is not portrayed as a common citizen, yet he is also not shown as a remote politician placed on a pedestal. While he is portrayed in a monumental size, sitting in a throne-like structure, with his clothing reminiscent of the robes found in classical statues, with his gaze slightly to the side and his clothes imitating that of a popular yet not austere s he embodies the image of a thinker and a philosopher. In this way, the statue carries through the classical Roman style inspiration that is present throughout the Franklin Institute’s dome, carrying with it the same visual messaging as well as serving as a tribute to Benjamin Franklin.

The Franklin Institute aims to provide a message of how the pursuit and advancement of science is a cornerstone of civic life and a shared human practice that should inspire wonder and curiosity. The Franklin Institute, through its various evolutions, including being one of the first museums in the US that invited hands-on learning, created a space where the public could actively engage with cutting-edge scientific ideas in a way that transformed them from abstract knowledge and discoveries to a collective pursuit of knowledge and progress by the nation.

Footnotes

-

Jmontefusco. “Benjamin Franklin Memorial.” The Franklrotundain Institute, April 12, 2024. https://fi.edu/en/exhibits-and-experiences/benjamin-franklin-memorial#:~:text=The%20Benjamin%20Franklin%20National%20Memorial,no%20admission%20fee%20is%20required. ↩

-

Mark, Robert, and Paul Hutchinson. “On the Structure of the Roman Pantheon.” The Art Bulletin 68, no. 1 (1986): 24–34. https://doi.org/10.2307/3050861. ↩

-

Jmontefusco. “Benjamin Franklin Memorial.” The Franklin Institute, April 12, 2024. ↩

-

Hannah, Robert, and Giulio Magli. “The Role of the Sun in the Pantheon’s Design and Meaning.” Numen 58, no. 4 (2011): 486–513. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23045866.= ↩

-

Britannica Academic, s.v. “Franklin Institute,” accessed November 24, 2025, https://academic.eb.com/levels/collegiate/article/Franklin-Institute/35188. ↩

-

Haviland, John (1792-1852) – Philadelphia Architects and Buildings. Accessed October 27, 2025. https://www.philadelphiabuildings.org/pab/app/ar_display.cfm/22166. ↩

-

Haviland, John (1792-1852) – Philadelphia Architects and Buildings. Accessed October 27, 2025. https://www.philadelphiabuildings.org/pab/app/ar_display.cfm/22166. ↩

-

Windrim, John Torrey (1866-1934) – Philadelphia Architects and Buildings. Accessed October 27, 2025. https://www.philadelphiabuildings.org/pab/app/ar_display.cfm/21563. ↩

-

Windrim, John Torrey (1866-1934) – Philadelphia Architects and Buildings. Accessed October 27, 2025. ↩

-

Wixom, Nancy Coe, and Martin Linsey. “Panini: Interior of the Pantheon, Rome.” The Bulletin of the Cleveland Museum of Art 62, no. 9 (1975): 263–69. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25152606. ↩

-

Mark, Robert, and Paul Hutchinson. “On the Structure of the Roman Pantheon.” The Art Bulletin 68, no. 1 (1986): 24–34. https://doi.org/10.2307/3050861. ↩

-

Linker, Jessica. “Franklin Institute.” Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia, March 17, 2022. https://philadelphiaencyclopedia.org/essays/franklin-institute/#:~:text=The%20new%20home%20of%20the,center%20for%20popular%20science%20education. ↩

-

McMahon, A. Michal. “‘Bright Science’ and the Mechanic Arts: The Franklin Institute and Science in Industrial America, 1824–1976.” Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies 47, no. 4 (1980): 351–68. ↩

-

Britannica Academic, s.v. “Franklin Institute,” accessed October 28, 2025, https://academic.eb.com/levels/collegiate/article/Franklin-Institute/35188. ↩

-

Britannica Academic, s.v. “Franklin Institute,” accessed October 28, 2025, https://academic.eb.com/levels/collegiate/article/Franklin-Institute/35188. ↩

-

McMahon. “‘Bright Science and The Mechanic Arts.” Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies 47, no. 4 (1980): 351–68. http://www.jstor.org/stable/27772696, 368. ↩

-

Thomas Coulson, “The Franklin Institute from 1824 tooperate 1949,” Journal of the Franklin Institute 249, no. 1 (January 1950): 1–48, https://doi.org/10.1016/0016-0032(50)90001-9, 1. ↩

-

Wolanin, Barbara A. “Italy’s Presence in the United States Capitol.” Essay,. ↩

Works Cited

Britannica Academic, s.v. “Franklin Institute,” accessed October 28, 2025, https://academic.eb.com/levels/collegiate/article/Franklin-Institute/35188.

Brown, Jack. “The Franklin Institute and the Making of Industrial America. Stephanie A. Morris.” Isis 81, no. 4 (December 1990): 1–74. https://doi.org/10.1086/355631.

Cohen, Jeffrey A. “Building a Discipline: Early Institutional Settings for Architectural Education in Philadelphia, 1804-1890.” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 53, no. 2 (1994): 139–83. https://doi.org/10.2307/990890.

Coulson, Thomas. “The Franklin Institute from 1824 to 1949.” Journal of the Franklin Institute 249, no. 1 (January 1950): 1–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/0016-0032(50)90001-9.

Hannah, Robert, and Giulio Magli. “The Role of the Sun in the Pantheon’s Design and Meaning.” Numen 58, no. 4 (2011): 486–513. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23045866.

Haviland, John (1792-1852) – Philadelphia architects and buildings. Accessed October 27, 2025. https://www.philadelphiabuildings.org/pab/app/ar_display.cfm/22166.

Jmontefusco. “Benjamin Franklin Memorial.” The Franklin Institute, April 12, 2024. https://fi.edu/en/exhibits-and-experiences/benjamin-franklin-memorial#:~:text=The%20Benjamin%20Franklin%20National%20Memorial,no%20admission%20fee%20is%20required.

Kelinich. “Mission & History.” The Franklin Institute, April 29, 2025. https://fi.edu/en/about-us/mission-history.

Linker, Jessica. “Franklin Institute.” Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia, March 17, 2022. https://philadelphiaencyclopedia.org/essays/franklin-institute/#:~:text=The%20new%20home%20of%20the,center%20for%20popular%20science%20education.

Mark, Robert, and Paul Hutchinson. “On the Structure of the Roman Pantheon.” The Art Bulletin 68, no. 1 (1986): 24–34. https://doi.org/10.2307/3050861.

McMahon, A. Michal. “Bright Science and the Mechanic Arts: The Franklin Institute and Science in Industrial America, 1824–1976.” Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies 47, no. 4 (1980): 351–68. http://www.jstor.org/stable/27772696.

“Atwater Kent Museum (Franklin Institute).” Sah Arcipedia, September 5, 2019. https://sah-archipedia.org/buildings/PA-02-PH41.

R. Guastavino Company, architects, John T. Windrim, and architects. Franklin Memorial and Franklin Institute Museum (Philadelphia, P.A.). n.d. Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library, Columbia University; Avery Drawings & Archives; Guastavino Fireproof Construction Company architectural records, 1866-1985; Series III: Project Files. Avery Drawings & Archives. Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library. https://jstor.org/stable/community.36129900.

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. “Franklin Institute.” Encyclopedia Britannica, August 18, 2025. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Franklin-Institute.

“The Franklin Institute.” JacobsWyper Architects. Accessed October 27, 2025. https://www.jacobswyper.com/projects/the-franklin-institute.

Windrim, John Torrey (1866-1934) – Philadelphia Architects and Buildings. Accessed October 27, 2025. https://www.philadelphiabuildings.org/pab/app/ar_display.cfm/21563.

Wixom, Nancy Coe, and Martin Linsey. “Panini: Interior of the Pantheon, Rome.” The Bulletin of the Cleveland Museum of Art 62, no. 9 (1975): 263–69. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25152606.

Wolanin, Barbara A. “Italy’s Presence in the United States Capitol.” Essay.