Palumbo's Item Info

- Title:

- Palumbo's

- Creator:

- Kenna Pettigrew

- Date Created:

- 11/25/2025

- Location:

- Palumbo's

- Latitude:

- 39.939643

- Longitude:

- -75.157635

- Rights:

- CC-BY 4.0

- Standardized Rights:

- https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Palumbo's

- Plumbo’s Boarding House

- South Philadelphia Nightlife: Palumbo’s Nostalgia Room and Restaurant

- Suspicion of Arson: The Demise of Palumbo’s

- The Philadelphia Rowhome: A Digression on Architectural Convention

- Modern-Day Palumbo’s: A Formal Description

- Critical Interpretation

- An Addendum on Images of Palumbo’s

- Footnotes

Palumbo’s is a famous name in south Philly, known as a bustling music venue of the mid-20th century, home to musical guests such as Frank Sinatra and Sergio Franchi.1 But before it was a nightclub, it was a boarding house that jumpstarted commercial activity in the 9th Street Market. Founded by Antonio Palumbo in 1884, the boarding house welcomed newly arrived Italian immigrants from the Washington Avenue Pier just nine blocks away from the still-extant market.

I chose to focus on Palumbo’s for my final project because, in the words of Beyond the Bell Tour guide Rebecca, Palumbo’s was, in its original form, a center for mutual aid for Italian immigrants to Philadelphia.2 Now more than ever, mutual aid informs a lot of the work I do in my personal life, whether that be volunteering, redistributing my money, or resource sharing. I knew that it was important to me to examine the mechanisms of mutual aid in the early life of the city of Philadelphia because many of these structures are still in place in the city today.

Plumbo’s Boarding House

Antonio Palumbo was a tailor from Abruzzo who likely immigrated to Philadelphia sometime in the 1880s.3 Other than that, not much is known about this inaugural generation of the family. Shortly after immigrating to the U.S. via the Washington Avenue Pier in Philadelphia, Antonio opened up a boarding house in his humble rowhome at 8th St and Catharine St in 1884. From then on, he welcomed newly arrived Italian immigrants in droves. Rumor has it Italians would show up to Washington Avenue Pier with slips of paper pinned to their clothes reading “Palumbo’s.”4 Boarding houses were especially prevalent in late-19th century Philadelphia, providing affordable meals and shelter to immigrants who had yet to find their footing in a foreign country.5 Once arrived at the house, Antonio and his son, Frank, would provide food, shelter, and laundry services to renters at a low cost of 90¢ per week. Boarders often cycled out once Antonio and Frank helped connect them to a job, usually in the mines, garment factories, or on the railroads. Under Antonio’s son, Frank, the residence continued to thrive, even surviving a federal investigation under suspicion that it was a padrone scheme. The government official that was sent to investigate this claim, Adrian Bronelly, reported that “a group of Italian American businessmen had ‘banded together to aid, comfort, and assist their brethren,’” and became a lifelong friend of the family.6

Today, the 9th Street Market Visitor Center still credits Palumbo’s as the flagship immigrant residence of the area: “The market began in the mid-to-late 1880s when Antonio Palumbo, an Italian immigrant, opened a boarding house in the neighborhood for other Italians. Businesses sprang up to serve this growing community and began to form the largest, outdoor, continuous market in the country.”7

South Philadelphia Nightlife: Palumbo’s Nostalgia Room and Restaurant

By the 1930s and ‘40s, boarding houses were beginning their fall from grace and were generally equated with living on “skid row.” Many boarding houses fell victim to gentrification projects, leaving former boarders without a place to live.8 It was around this time that Frank Sr. (the second in a line of men named Frank Palumbo) began to set his sights higher for the family business.

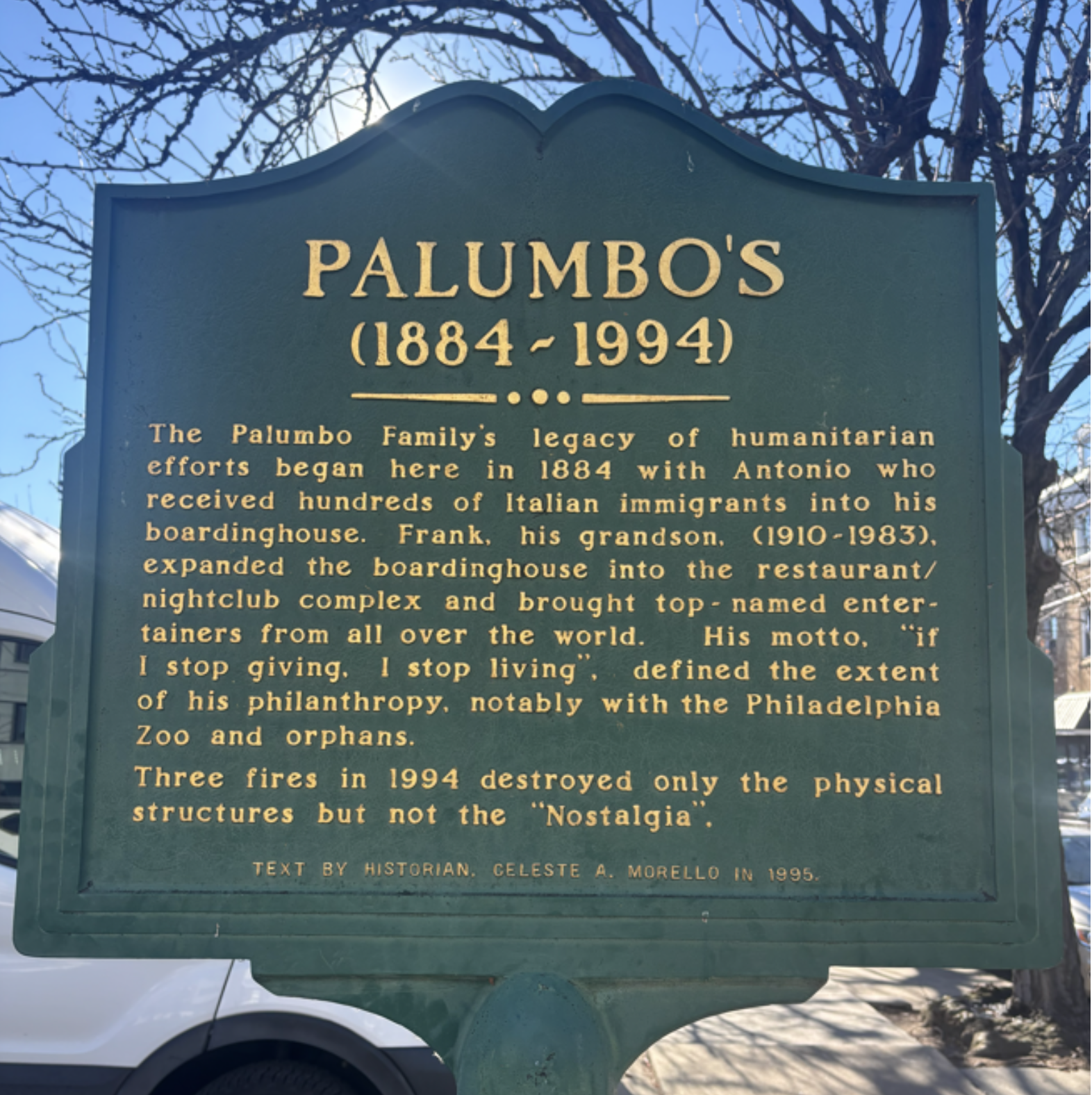

Frank Sr.’s father committed suicide and left him with the business when he was fifteen, meaning that he was no stranger to how much elbow grease it took to keep the boarding house running. He wanted to take his family’s philanthropy to new heights, and there are several corroborated reports that say he routinely took orphans on outings to the circus or the zoo. According to journalist Ralph Cipriano, “These excursions were highly publicized by reporters who ate and drank for free at Palumbo’s, had $20 bills stuffed in their pockets, and cases of liquor delivered to their cars.”9 As a result, his reputation thrived, and it is around this time that he was quoted as saying “If I stop giving, I stop living,” a quote that appears on the Palumbo’s historical marker today (Fig. 1).

Frank Sr.’s rise in fame gave him the momentum he needed to turn Palumbo’s into a restaurant and nightclub, eventually expanding what began as a humble boarding house into a complex of several rowhomes. The new complex contained a banquet hall, where anyone from a local politician to a famous musician could put on a show, as well as the famous “Nostalgia Room,” which is also referenced on the Palumbo’s historical marker. Rumor has it that the expansion he did of Palumbo’s wherein he overtook the surrounding rowhomes was actually illegal, but he evaded penalization by lining the pockets of city officials.10

In the heyday of Palumbo’s restaurant and Nostalgia Room, they booked big names such as Frank Sinatra, Billy Ruth, Kenny Adams, Sergio Franchi, Al Martino and the Mills Brothers, and Jimmy Durante.11 It was also during this time that, it can be said, Palumbo’s departed from the business’s original pathos as a boarding house and center for social work. Rereading accounts of the life of Frank Sr. certainly maintains that he was the philanthropist he was perceived to be during his lifetime, but people also do not shy away from being candid about his showmanship. Eyewitnesses report that “Everything he did was big,” and that before shows, he would roam around the banquet hall giving away expensive goods such as bottles of perfume or watches to returning guests.

In a saccharine testament to maintaining the community that began to form at Palumbo’s, Frank Sr. hosted an annual Valentine’s Day dance where he invited all of the couples that had held their wedding receptions at Palumbo’s in the past year. Cipriano writes, “He’d serve his guests filet mignon and champagne on the house, and serenade them with strolling violinists.”12 In its heyday as a nightclub, Frank Sr. made the place what it was.

Suspicion of Arson: The Demise of Palumbo’s

In July of 1994, Palumbo’s Restaurant and Nostalgia Room spontaneously caught fire; the blaze rampaged an entire city block thanks to four open fire doors (a breach of fire code, to be sure). While articles from the Philadelphia Enquirer and the Philadelphia Daily News cite suspicion of arson, neither of the property owners (Frank Palumbo Jr. and his business partner Lee Esposito) had fire insurance, and therefore could not file a claim to refurbish the building after extensive damage. The press reports that many employees, especially the ones working the night before the fire, were subject to questioning from the authorities. The police eventually made two arrests, but both suspects were eventually dismissed. The mystery of who could have started the fire that burned up a whole city block was never solved, and neither Frank Jr. nor his business partners made a concerted effort to clean up the mess. The stench of rotting meat from the thawed freezers filled the neighborhood, with a gnat infestation to follow. In August, scavengers began raiding the ruins of Palumbo’s and partying in the condemned building late into the night. George Galdi Jr., a member of the neighborhood community, remarked, “It’s like the place’s got a curse on it.”13

On January 4, 1995, Frank Jr. and Lee Esposito sold the property to new owners who had ambitious plans to build a Rite Aid pharmacy (Fig. 2). The Rite Aid still occupies the lot today, but is now vacant following the company’s 2023 file for bankruptcy.14 The unofficial historical marker for Palumbo’s stands humbly in an untended flowerbed.

The Philadelphia Rowhome: A Digression on Architectural Convention

At the turn of the 19th century, a scale model of a rowhome was displayed at the Chicago World’s Fair with the title “The Workingman’s House.”15 The house in question would have been a standard accessible housing option for Philadelphians of all class strata, and could be scaled up or down depending on how much square footage an inhabitant could afford. In an era where nationwide housing options for the working class included the cramped and often inhumane tenement house, the Philadelphia rowhome was an appealing alternative.16

On the smaller end of the spectrum is the trinity, a rowhome so named because its configuration is three rooms stacked atop one another to form a single-family dwelling. Due to its small size, the trinity was the most affordable and could accommodate working-class families on plots of land no more than 16 feet wide. The largest dwelling to be considered a rowhome would have been the town house, which is two rooms deep and also accommodates a small yard in the rear. Within the title of the rowhome, Philadelphia maintained a relatively homogenous urban landscape that accommodated families of all different class strata. Additionally, property buyers could efficiently and cost-effectively construct many rowhomes by buying standardized materials in bulk and constructing them in compounded structures rather than freestanding. It is for these reasons that the rowhome became such a hallmark of Philadelphia’s urban landscape, and hundreds of rowhomes are still standing across the city today.17

Based on extant photos of Palumbo’s, the boarding house likely would have started in a single-family rowhome belonging to Antonio Palumbo and his family. While I have been unable to locate specific information on the rowhome model that the Palumbo family would have started out in, I would hazard a guess that it was a mid-size model based on the fact that the family would have needed the space to host boarders, and later convert the space into a concert and nightclub. I do not believe that either of these social ventures would have been possible in a rowhome as small as a trinity simply because these structures have very limited depth. Therefore, It is most likely that the Palumbo’s original rowhome was a city house plan, which was an expansion on the trinity plan and included designated rooms for services such as cooking and laundry.18 Both of these services would have been provided to boarders at Palumbo’s.

Modern-Day Palumbo’s: A Formal Description

he only image I have been able to access of Palumbo’s looks to have been taken shortly after the building was destroyed by fire in 1994. The photo shows a series of three rowhomes that encompass the interior’s two banquet halls and the famous “Nostalgia Room.” The facades of the rowhomes are flat, with the one on the far left constructed out of red brick. The two central rowhomes alternate in a pattern of white and grey brick, with a neon sign above the main entrance that reads “Palumbo’s Nostalgia Room and Restaurant.” Above the customer entrance to the door, there is a red awning that covers a small set of front steps. The fourth and final rowhome to the right of the front entrance looks to also be made of brick in a different color variety than the rowhome on the far left. True to rowhome form, each of these parts in the series maintain the exact same physical structure, if differing slightly in aesthetic.

For additional information on locating photos of Palumbo’s, please see the addendum at the end of this article.

Critical Interpretation

Perhaps the most compelling part of Palumbo’s story is the way the business changed throughout the many generations of this very important family. Originating as a center for mutual aid and social services to newly arrived migrants, the original message of Antonio Palumbo was to look out for your fellow immigrants and ensure that you pay it forward and make life in America easier for those that come after you. However, as the business was handed down, these philanthropic gestures became more self-servient in that their purpose was to bring the family name greater fame and money in the local community. This is not to say that all good intentions evaporated, but it seems as though Frank Sr.’s grand public gestures towards young orphans signified a misalignment with his grandfather’s original mission – and that misalignment would only grow as his business knocked down single-family rowhomes to make room for his growing enterprise.

As Rebecca of Beyond the Bell Tours noted as we walked the streets of the Italian Market, the property’s eventual sale to a Rite Aid franchise is part of a more concerning trend of multi-generational family business to sell. Most recently, Di Bruno Bros., a renowned Italian bakery, sold to someone outside the family, raising concerns for locals about possible gentrification of the area that poses a threat to the autonomy of immigrant communities in the phase of larger corporate conglomerates. I can only hope, as Antonio Palumbo might have, that the neighborhood remains a place where a newly-arrived migrant can be taken care of by a community that encourages them to establish the life they want in a new country.

An Addendum on Images of Palumbo’s

The only extant photos of Palumbo’s that are readily available exist on informal forums and social media sites such as Reddit and Facebook. These photos are not licensed under Creative Commons, and are therefore not reproducible on webpages without consent from the original poster, but a photo of the exterior of Palumbo’s shortly following the fires in 1994 is available here

Footnotes

-

Ralph Cipriano, “Frank’s Place, The Philadelphia Inquirer (Philadelphia, PA), Jan. 29, 1995. ↩

-

Rebecca Fisher (Beyond the Bell Tour Guide), in discussion with the author, October 2025. ↩

-

Cipriano,“Frank’s Place.” ↩

-

Cipriano,“Frank’s Place.” ↩

-

Wendy Gamber,“Boarding and Lodging Houses,” accessed November 24, 2025.https://philadelphiaencyclopedia.org/essays/boarding-and-lodging-houses/. ↩

-

Cipriano,“Frank’s Place.” ↩

-

“The Nation’s Oldest Outdoor Market, ” Italian Market Philly, accessed November 24, 2025. https://italianmarketphilly.org/history-2/. ↩

-

Gamber, “Boarding and Lodging Houses.” ↩

-

Cipriano, “Frank’s Place.” ↩

-

Cipriano, “Frank’s Place.” ↩

-

Cipriano, “Frank’s Place.” ↩

-

Cipriano, “Frank’s Place.” ↩

-

Cipriano, “Frank’s Place.” ↩

-

Kate Reilly and Madison Lambert “Rite Aid shutters all stores after years of financial struggles,” NBC News, Oct. 4, 2025. https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/rite-aid-closes-stores-nationwide-rcna235596. ↩

-

Christine Speer Lejeune, “The Rowhome Is Us,” Philadelphia Magazine (Philadelphia, PA), April 3, 2016. ↩

-

Lejeune,“The Rowhome Is Us.” ↩

-

Amanda Casper, “Row Houses,” accessed Nov. 24, 2025. https://philadelphiaencyclopedia.org/essays/row-houses/. ↩

-

Casper, “Row Houses.” ↩

Works Cited

Casper, Amanda. “Row Houses.” Accessed Nov. 24, 2025. https://philadelphiaencyclopedia.org/essays/row-houses/.

Cipriano, Ralph. “Frank’s Place.” The Philadelphia Inquirer (Philadelphia, PA), Jan. 29, 1995.

Gamber, Wendy. “Boarding and Lodging Houses.” Accessed Nov. 24, 2025. https://philadelphiaencyclopedia.org/essays/boarding-and-lodging-houses/.

Lejeune, Christine Speer. “The Rowhome Is Us.” Philadelphia Magazine (Philadelphia, PA), Apr. 3, 2025.

“The Nation’s Largest Outdoor Market.” Italian Market Philly. Accessed November 24, 2025. https://italianmarketphilly.org/history-2/.

Reilly, Kate and Madison Lambert. “Rite aid shutters all stores after years of financial struggles.”

NBC News. Last modified October 4, 2025, https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/rite-aid-closes-stores-nationwide-rcna235596.